Disclaimer:

I don't like snake oil salesmen, or baby/bath water tossers.

*****

When you're a first year teacher, you listen, nod, and soak up as much as you can from your colleagues. You wonder, you ask, you adopt, you go through the motions, you borrow, and you spend weekends in your classroom. In many cases, you put on your interpretation of the costume and attempt to wear the bearing of a fellow teacher, master educator, or inspiring person from your past. Carefully navigating the hallways, meetings, and conversations in which you find yourself, you act "as if:"

as if you have some sort of experience,

as if you have a clue,

as if you know what you're doing,

as if you're not afraid. You act

as if because you're a newbie and you likely don't have a clear cut plan about how to handle every component of the learning environment entrusted to you. You haven't yet built professional relationships with those with whom you work most closely, and in fact, you

are scared.

After four or five years of teaching, you're no longer the newbie, but you don't have a long history of educating others. You remember that girl in your first class, that boy in your third year of teaching, or that family from last fall. Your history of public education is still colored more by your memory of being a student than of being a teacher. Perhaps you've served on a committee. As a result, you still ask questions, and you listen intently to seasoned colleagues as they discuss, debate, and even argue the finer points of curriculum development, societal influences, administrative mandates, budget concerns and education reform. You're learning to discriminate between the complaints from burnt out staff members who have passed their prime, the storytelling from older colleagues who "remember when," and the wisdom of those highly qualified teachers who can not only recount what happened the last time change was implemented, but share the merit of the evolution, or warn of the failures that inevitably happened when a grade level, school, district, state, or nation decided to throw the baby out with the bath water.

Stories from many of your colleagues will likely fascinate you, make you question what it is you really know, and from time to time, will have you looking at the clock, wondering if there's some way you can politely excuse yourself. Recitations of history are tough when what you want or need is the quick-fix, the yes/no answer, the band-aid that you can peel and apply before the buzzer goes off, ending this round of How-Will-You-Handle-This-Successfully-Because-the-Principal-is-Probably-Watching-and-Yes-This-WILL-Be-Noted-on-Your-Teacher-Evaluation. You like discovering the black and white, and you commit yourself to them, because gray zones are still tricky to navigate. You're relieved to no longer be a first year teacher, and you can now share your opinions much more freely, though they reveal the experiential, even generational divide that still exists between you and your older colleagues. Congratulations: you can now walk and chew bubble gum at the same time.

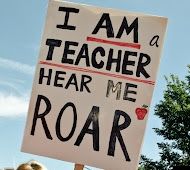

Year after year will pass, and not only will you recognize and respect those who have gone before you, you'll be more giving of yourself with both new-to-service teachers and those colleagues who truly embody what it is to be lifelong learners. Those highly qualified folks still won't like snake oil salesmen, and it's likely they'll appear resistant to change, with higher ups accusing them of digging in their heels and labeling them "old school," or "out of touch with the times." You might even be encouraged to maneuver around those "old fogies," and to ignore the fact that they've taught long enough, lived long enough, and learned enough to know some inherent truths about the profession and the children it's meant to support. My advice? Learn from your colleagues. Respect your elders. Stay in the profession, and grow to be one of us. Now, more than ever, our students and schools need highly qualified child advocates and "leaders in education"

who have actually taught.

*****

After eighteen years of teaching, here's some of what I know:

Differentiation used to reference the practice of teachers addressing differences in age and the development and learning styles of their students. Today,

differentiation must include factors such as home life, medical issues, socio-economic status, personality, special needs, developmental delays, dietary restrictions and cultural practices.

While the tools we use in the classroom are largely mechanical, our students and the learning they do are living, organic beings and processes. The developmental stages that most children work through and build upon can be tracked and identified, yet the pacing of each child's trek through them cannot be plotted out on a predictable timetable: some children walk at nine months of age, others twelve. Some children don't take their first steps until they're fifteen or seventeen months old. Some children read at age four, while others are bitten by the book bug at age six or later. Some children require new shoes and pants in the fall, while others sprout when spring arrives. As a teacher, you must deliver the curriculum between August and May, despite the fact that children don't work through the introduction and exploration of new concepts, nor do they make connections between or demonstrate mastery of skills at a pace of five per day, precisely between eight a.m. and four p.m. This discrepancy will not prevent the powers that be, parents, or much of society as a whole from blaming you for a child's earned grades: they want mastery, and they want it now. It will also not prevent snake oil salesmen and women from trying to convince adults that if we want little Jamie or little Johnny to grow up to be a surgeon, we should put scalpels into their hands at age five. No, four. Next year, they'll insist that scalpel introduction should happen at age three. Don't you know, earlier is better?

Education reformers who prefer measured, methodical, and rhythmic "growth" need to be honest with the public: they don't respect or even like children. They view childhood as an affliction, something to be cured, and the faster the cure arrives, the better. Machines are programmed to perform or produce one task or product, while human beings have the capacity to imagine, create, grow into and inspire almost anything. Advocates of industry don't often make the best advocates for children.

Every child is different, yet somehow, the expectation of parents, newer teachers, some administrators and many politicians is that students can be the same, and by a certain date,

should be. Ignoring, or pretending that dynamic nature/nurture variables don't really exist won't change the fact that for best results, we should be teaching the way children learn best, instead of following some scripted drivel that lacks in spontaneity and joy while squashing inquiry and creativity. By the way: every teacher is different too.

Revisit how you felt the first time you were observed and evaluated by your administrator. Now remember the second time. Perhaps you're going to be evaluated this week. Maybe you've been placed on an improvement plan, requiring many more visits, both surprise and scheduled. What level of stress do you feel in these situations? Slight? Fair to middling, or pass-the-Xanax-please? If you experienced toxic stress in the workplace, how would you perform? Now, imagine you're a child experiencing multiple years' worth of performance and test anxiety, and you're not yet old enough to have an arsenal of stress relieving strategies at your disposal. How would you function? Would you act out? Be fidgety? Emotional? Reluctant? No wonder many parents, teachers, and child advocates

liken the annual barrage of standardized testing (and the days, weeks, and months of "test prep" that usually accompanies it) to child abuse.

It's not weak or wrong to care about children, the environment in which they learn, and the people with whom they interact. It's responsible and appropriate to place highly qualified educators in mentorship roles, and give them ample opportunities to work and grow with their grade level and team members. It is also essential that veteran teachers be asked for their input, opinion, suggestions and leadership when "education reform" comes knocking on the door. They've got the history because they've lived it, they're truly invested in their profession, and they know not to throw the baby out with the bath water when someone strongly resembling a con artist offers their staff "professional development and support products" while waving a bedazzled poster board proclaiming "There's something terribly wrong with children- they're stuck in childhood! Buy my product, and your problem will be gone by May 31!"

Fear mongering is a tactic of the greedy. Thoughtful consideration and calm, thorough evaluation are

behaviors of the educated.

*****